In Vitro – In The Future?

Andrew Dickson, the general manager of Manitoba Pork, is one of the brightest people in Canada’s meat industry. He always has his fingers on the issues of the day and he always provides an interviewer with a scientifically-based, measured assessment of all things new, old and even controversial in the industry

a Canadian Meat Business exclusive by Scott Taylor

But when we asked him about the concept of “in vitro,” or “cultured meat,” he had no answer.

“I know little or nothing about these developments,” Dickson said. “I don’t want to comment on them without doing a lot of research.”

Dickson was not alone. While the idea of in vitro, cultured or what’s called, “clean meat,” by its supporters, is not new, the fact that it is now closer to market than ever before seems to have come as a surprise to some people in the beef, pork and poultry industries in Canada.

According to Uma Valeti, a co-founder and the chief executive officer of San Francisco-based Memphis Meats, cultured meat has been on the minds of food scientists for decades, but only now, thanks to the help of financing from people such as Sergey Brin, Richard Branson and Bill Gates, does there appear to be a realistic date in which to get the product to market.

“We’re not there yet,” Valeti acknowledged, “but in just a few years, we expect to be selling protein-packed pork, beef and chicken that tastes identical to conventionally raised meat but that is cleaner, safer and all-around better than meat from animals grown on farms.

“We identify cells that have the capability to renew themselves. We breed those cells that are the most effective and growing — just like a farmer would do with animals.”

“European Union closed the door on imports of hormone-treated beef in 1989”

If true, that could be either the end of cattle ranches and pig farms or simply become an extension of a meat industry that has never been busier, more successful or with more products in demand that it has today.

On Labor Day Weekend, the Third International Conference on Cultured Meat was held at Maastricht University in the Netherlands. The goal of the project at Maastricht is simple:

“The world faces critical food shortages in the near future as demand for meat is expected to increase by two-thirds, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

“The production of meat through tissue culture could have immense effects in reducing the environmental impact of our agriculture system, minimizing threats to public health, addressing issues of animal welfare, and providing food security.

“Cultured Meat represents the crucial first step in finding a sustainable alternative to meat production.”

Meanwhile, Maastricht University’s scientists describe Cultured Meat this way:

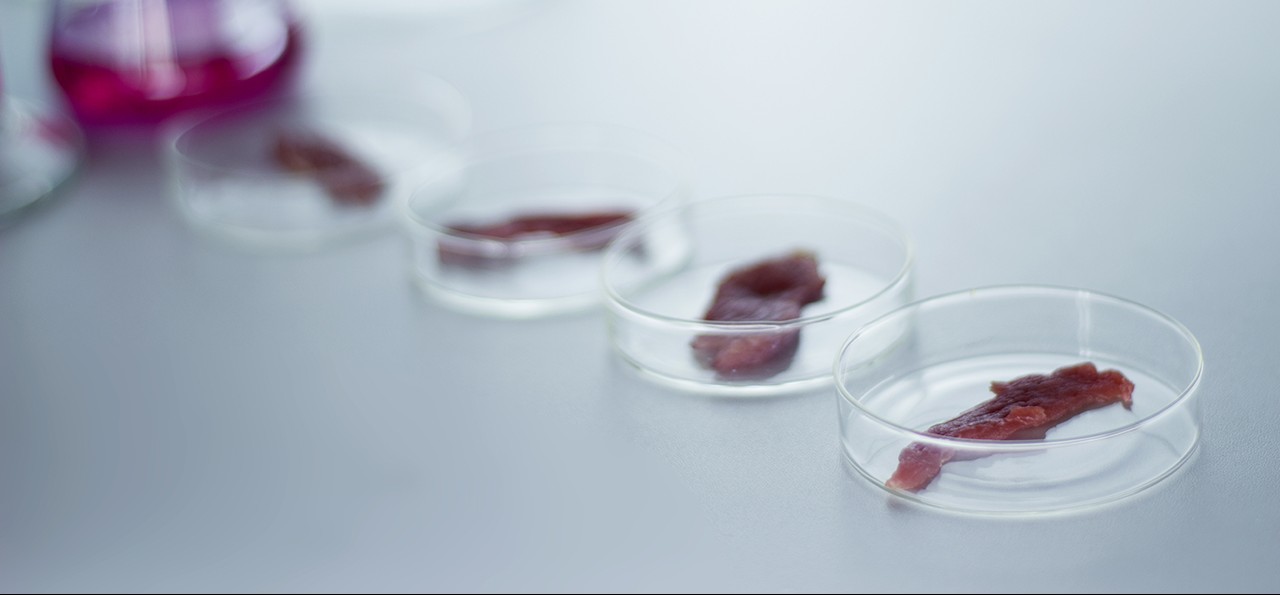

“Cultured Beef is created by painlessly harvesting muscle cells from a living cow,” the Dutch scientists explained. “Scientists then feed and nurture the cells so they multiply to create muscle tissue, which is the main component of the meat we eat. It is biologically exactly the same as the meat tissue that comes from a cow.

“The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) estimates that the demand for meat is going to increase by more than two-thirds in the next 40 years and current production methods are not sustainable. In the near future both meat and other staple foods are likely to become expensive luxury items, thanks to the increased demand on crops for meat production, unless we find a sustainable alternative.

“Livestock contributes to global warming through unchecked releases of methane, a greenhouse gas 20 times more potent than carbon dioxide. The increase in demand will significantly increase levels of methane, carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide and cause loss of biodiversity. Cultured Beef is likely a more sustainable option that will change the way we eat and think about food forever.”

In a study undertaken in 2011 by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, it was estimated that the demand for meat in North America will increase by eight percent between 2011 and 2020, in Europe by seven percent and in Asia by 56 percent. Meanwhile, that same study calculated that growing meat in labs would cut down on the land required to produce beef, poultry and pork by 99 percent and reduce the associated need for water by 90 percent. What’s more, it found that a pound of lab-created meat would produce much less polluting greenhouse-gas emissions than is produced by cows, pigs, chickens and turkeys.

Sounds great, of course, but there are still two important questions – what does it taste like and how much does it cost?

Ryder Lee is the CEO of the Saskatchewan Cattlemen’s Association. He’s been following the progress of Cultured Meat for a long time and while he’s not worried about it ending the cattle industry in Canada – or anywhere else, for that matter – he always tells his members to be aware of its existence.

“We’ll wait and see, I guess,” Lee said philosophically. “With Cargill investing in it, it is a good poke to anyone in the meat value chain, not to be complacent. Competition isn’t new for the beef, pork and poultry industries, and this is another product being developed that might be in competition with what we do.“It’s certainly going to be part of the future of the industry, but when will that be? Star Trek and the Jetsons predicted we’d have flying cars long before now and we still don’t. We know it’s out there, but when it becomes a viable product on the market is anybody’s guess.”

To be fair, Winston Churchill wrote an essay in 1932 that claimed, “Within 50 years we’ll be growing edible animal parts to escape the absurdity of growing a whole chicken.”

He was off by only 20 years. In 2002, a NASA-funded project successfully grew fillets from goldfish cells, but it wasn’t until about a decade later that lab-grown meat began to look scientifically and economically viable.

Medical science has, for decades, been working on generating human organs from stem cells, but while taking those principles and moving them to the beef, pork and poultry industries has been a dream of many in the scientific community, it was always just a bit of Star Trek science fiction.

However, in August of 2013, when those scientists from Maastricht University, led by Professor Mark Post and funded by Google co-founder Sergey Brin, conducted a public tasting of a hamburger cultured out of beef muscle stem cells, the concept became real – if not at all a marketable product.

“Close to meat, but not that juicy” was one public taste tester’s verdict.Oh, and there was one other problem. The total price tag on the hamburger experiment was a whopping $330,000 US.

Still, as Lee says, “Motivated minds are working the idea non-stop and it will be a gold mine if you can solve it.”

And, indeed, there are people all over the world trying to make it work.

Michael Selden of Finless Foods is trying to replicate fish filets. His team just began work on creating Bluefin tuna using a biotech accelerator in San Francisco.

“There are so many things that animals do that we don’t need them to do in order for them to be food for us,” Selden told Forbes Magazine. “Eyeballs: What are they good for? Fish guts: potentially toxic. The energy required to grow feed for cattle and raise them until slaughter has been estimated at 25 calories expended per one calorie of energy contained in beef.”

Meanwhile, back at Maastricht, Post claims he has the price of the burger down to $11 US and the cost of his cultured beef to $30 US a pound.

Perhaps the best-known and seemingly most advanced company in the field is Valeti’s Memphis Meats. With much fanfare, it debuted a cultured beef meatball in 2016 and in March of this year, it held a taste testing in San Francisco for cultured duck a l’orange and cultured fried chicken.

“The challenges are finding the cells that are the highest quality in terms of nutrition, protein content, fat content, taste and texture,” Valeti told the San Francisco Chronicle.

“The way the cells grow and the way we cultivate and harvest them is different for each species. A major breakthrough in texture for us was developing a cultivation process that allows us to harvest bulkier strips of chicken and duck. This opens up opportunities to develop thicker cuts of meat like steaks.”

According to Valeti, Memphis Meats’ goal is “to be on the market in five years,” although it will still be quite expensive. Right now, one pound of beef from Memphis Meats costs $18,000 US to grow.

“In the next 10 to 20 years we want to have Memphis Meats be accessible to seven billion people across the world,” Valeti told the Chronicle. “That way they can still have the delicious meat that their cultures support, but eat meat with their eyes wide open, not worrying about where it came from.”

And that’s an issue that interests Ryder Lee at the Saskatchewan Cattlemen’s Association. The projections on world protein growth coming from the UN are based almost entirely on population growth. According to the FAO, “Population growth and changing trends in diet have led to a doubling of meat consumption by humans over the past half-century. By 2050, estimates suggest meat production will have to increase to 455 million tons each year, up from 259 tons today, in order to satisfy the additional demand generated by population and income growth, according to a 2012 report by the United Nations.”

With that in mind, Lee doesn’t fear cultured meat as much as he sees it as a supplement to “real beef.”

“Much of what I read and hear about this lab-grown beef is that it will be quite some time before it gets to market,” he said. “When it does, I wonder if, instead of being a substitute for our beautifully grown Canadian beef, it will be a supplement. I agree that around the world, there is a growing demand for Canadian meat. When you look at the beef we produce, it’s a product that people all over the world want on their tables. But there are many places on earth that can’t get access to what we breed and grow here in Canada – or at least, not access to enough of it. If the people working on this cellular product can make it affordable, I can see it as a perfect supplement for the developing world.”

Memphis Meats creates its meat – that comes from the cells of cows, pigs and chickens — in a lab and currently, one meatball takes about three weeks to develop in a steel tank. The cells themselves are “fed” a diet of glucose, vitamins and minerals in order to proliferate.

“It’s not ‘lab-grown’ meat,” said Valeti, in a written statement. “It’s like a meat brewery. We create the conditions where the cells can grow freely.”

So how does it taste?

“It has an undeniable and intense meat flavor,” Valeti’s statement added. “Our goal was not to be a vegetarian product. We’re trying to scale it up so that it’s cost-effective. We hope to sell our product by 2021, but we’re still deep in R&D.”

Besides the scientists in Maastricht (Mosa Foods) and Memphis Meats, there are a number of other startups in this developing industry. Beyond Meat, which makes protein from plants, has garnered its financial support from Microsoft’s Bill Gates and two Twitter co-founders. Gates also backed Beyond Meats’ rival, Impossible Foods.

“You can’t get people to stop eating meat,” said Pat Brown, the founder and CEO of Impossible Foods, in a written statement. “We turn plants into meat more efficiently and sustainably than animals. A cow is pretty much as mature a technology as it will ever be. One of the huge advantages we have over cows when it comes to making meat is we have the capability of improving every aspect of it.”

There is now a turkey cell line, which was used last year to grow a small turkey nugget at North Carolina State University, by graduate student Marie Gibbons. Memphis Meats has created the world’s only chicken nuggets grown entirely in a steel tank.

And recently, a company called Modern Meadow has promised that lab-grown steak chips — a product that is part potato chip and part beef jerky — will also reach the market soon. Not sure about that one.

Still, with Cargill involved, even major U.S, meat producers have taken some interest. In December of 2016, Tyson Foods, the largest U.S. meat company, launched a venture- capital fund to invest in start-ups that “work on innovative approaches to protein products.”

The goal, of course, is to eliminate the need to feed, breed and slaughter livestock, but based on everything we’ve read, that’s at least 50 years away — if not 100.

“Meat demand is growing rapidly around the world,” added Valeti, in a written statement. “However, the way conventional meat is produced today, it creates challenges for the environment, animal welfare and human health. We’re going to bring meat to the plate in a more sustainable, affordable and delicious way. It’s coming and we believe it will arrive sooner than people think.”

Our April 2024 Issue

In our April 2024 issue we feature, Harvey’s celebrates 65 years, the annual Power of Meat Report, bird flu poses challenges for meat producers, FCC reports improved margins for 2024, U.S. meat labelling rules causing concern, support for temporary foreign workers, navigating Bill-C-58, and much more!